Demand Me Nothing: What You Know

Washington State Academy

Human action V

SCENE i

Iago hides Roderigo in preparation for the ambush on Cassio. Iago privately admits that whoever kills the other, information technology's all good, but all-time if they both are dead. Cassio comes past, and Roderigo attacks, but Cassio wounds Roderigo. Iago secretly, from behind, attacks and wounds Cassio in the leg. (De Vere received a leg wound in an attack by Knyvet and his men in the early 1580s.)

Othello hears the noise and thinks Cassio is a goner. He too probably thinks that Roderigo'south complaining, "O, villain that I am!" (5.i.29), is really Cassio albeit his guilt, and thus mutters, "It is even then" (5.i.29), as Goddard points out (Goddard, Two 93). In the racket and confusion, Iago takes the opportunity to stab Roderigo, who dies saying, "O damn'd Iago! O inhuman canis familiaris!" (V.i.62). Iago then pretends business concern for Cassio. When Bianca chances upon the scene, Iago takes advantage of the same kind of flim-flam he's been using all along; he tries to arraign her and take the others read guilt into her behavior. Iago'due south final line suggests he thrills at the adventure of all this: "This is the night / That either makes me, or foredoes me quite" (V.i.128-129).

SCENE 2

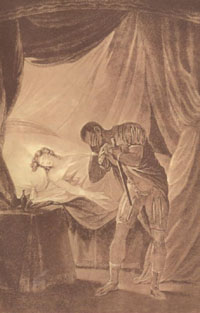

Othello enters the sleeping room and says, "Put out the light, and so put out the light" (Five.two.vii), referring to the candle and Desdemona'south life (and maybe reason itself, unintentionally). He kisses her and seems in control again, admitting that of a priest at sacrifice. He notifies her what is coming and smothers her, presumably with a pillow.

Emilia is at the door with news of the doings outside: Roderigo is dead, but when Othello learns that Cassio is not, he remarks, "Not Cassio kill'd? Then murther'south out of tune" (V.ii.115). Emilia hears Desdemona moaning, but Desdemona protects Othello, jeopardizing her soul past lying -- saying Othello did not impale her. Emilia and Othello contend, and when Othello insists Iago knew the sordid truth too, Emilia can only echo, "My husband?" (V.ii.140, 146, etc.). Emilia gradually realizes the truth and calls Othello a "gull" and a "dolt" (V.ii.163). She confronts Iago when he arrives, and the concern most the handkerchief comes out, making Emilia recognize that attribute of the plot. Iago calls her "Villainous whore!" (V.ii.229). Othello charges at Iago only is disarmed. Iago kills Emilia, who dies insisting Desdemona loved Othello.

| The question of Desdemona's murder has prompted lots of speculation. If she was strangled, why tin can she speak nonetheless and why is she called "pale" instead of purple? Southward. Weir Mitchell, the "nerve specialist" Charlotte Perkins Gilman skewered in The Yellow Wallpaper, asserted that Othello choked Desdemona insufficiently so finished her off with a dirk. Goddard agrees that Othello did a poor job at strangulation and so he stabs her when he is saying "So, so" (V.ii.89). Or does Desdemona recover but die of a broken heart, or is information technology a "fracture of cricoid cartilage of the larynx [?] ... Tracheotomy was the only thing that might accept saved her.... Is not Shakespeare's universality wonderful?" (qtd. in Sutherland 36). And by the fashion, every bit Marilyn French points out, "if Desdemona had been inconstant, would she have deserved death? Does Othello have the right to kill her if she is guilty? He [Shakespeare] does not deal with these questions in Othello, because this play is about male attitudes towards women -- and each other -- and thus Desdemona must stand as a symbol of what men destroy" (French 219). |

Somehow, Othello has another sword in the room and when Iago is captured and brought forth, Othello wounds him. "I drain, sir, but non impale'd" (V.ii.288). Othello asks why he did all this, to which Iago replies, "Need me goose egg; what you lot know, you know: / From this time forth I never will speak word" (5.ii.303-304).

Thus Iago pleads the Shakespearean fifth and lapses into silence. Is he silent because no lies are possible now and that was his only mode of expression? Or is this the artistic impulse for perfect proper completion. He spoke of his plots as children, indicating a sort of creative energy pervertedly invested. His piece of work here is done -- and so there'south nothing more to say that wouldn't seem like a inexpensive coda. His was the perfect work of anti-art, so there'southward no more voice, no more identity outside that role as anti-creative person.

| Cassio explains what he knows as Othello suffers his ain awareness. "Othello, all the same, has ane concluding thing to say. With an effort, he manages to pull himself together into most the man he in one case was and speaks once more, a piffling in self-pity, much more in self-detest. He asks them all to tell the tale honestly" (Asimov 631). Othello'southward first assertion -- "I have done the state some service, and they know 't" -- is grossly inappropriate to a murderer's testimony and, so, awkwardly inserted and immediately dismissed. Just, autobiographically, information technology fits the hypothetical hushful-up hush-hush-service-funded 1000-pound-annuity scheme to accept Oxford boost national pride through his pro-England, pro-Tudor edutainment. I pray you, in your letters, |  |

Othello ends his final oral communication:

... a cancerous and a turban'd TurkOthello pictures himself as a Turk, every bit ane of his ain enemies, which he did indeed go to himself. "'Uncircumcised canis familiaris' was a common derogatory phrase for Christians among Moslems, indicating that they were outside the pale of the true faith. Othello's employ of the opposite phrase in his last desperation is like a return to his origins" (Asimov 632). Yet, he dies speaking of himself in the third person, perhaps signifying -- simply in a mode controlling -- his lost identity. He stabs himself, falls on the bed, and dies. Along with Iago, nosotros "Look on the tragic loading of this bed" (5.ii.363).

Beat a Venetian and traduc'd the country,

I took by th' throat the circumcised dog,

And smote him -- thus.

Almost critical attending, naturally, is paid to Othello's 19-line speech here, a "famous and problematic burst" (Blossom 474), alternately considered a regaining of the character's "magnanimity and ease of command" (Wells 250) or a demonstration of "obtuse and fell egoism" (F.R. Leavis, qtd. in Wells 258). Every bit Stanley Wells puts information technology,

The bones question raised by the play's closing episodes is whether Othello remains a animate being or recovers his manly stature. Or, to put it in theological terms, whether he is destined for damnation or 'saves himself' by acknowledging his crime, repenting it, and punishing himself for information technology. (Wells 256)Samuel Johnson called it, ambiguously, "this dreadful scene; it is not to be endured" (qtd. in Garber 615). Neutral or somewhat forgiving critics emphasize Othello's "self-exculpation," declaring information technology a speech "of self-condemnation, and it culminates in self-execution" (Wells 257). Despite his crimes, "He dies in the act of describing a noble public gesture, the killing of a public enemy" (Garber 615). Other critics have been harsher. T.S. Eliot claimed in 1927 that he had "never read a more terrible exposure of human weakness -- of universal homo weakness -- than the last swell speech of Othello" (qtd. in Wells 257). F.R. Leavis influenced Laurence Olivier's 1964 performance, after which Dover Wilson protested the delineation of "an Othello in which he 'could discover no dignity ... at all, while the finish was to me, not terrible, but horrible beyond words'" (qtd. in Wells 258). Harold Blossom, although he bemoans "a bad modernistic tradition of criticism" from T.S. Eliot to F.R. Leavis and New Historicism that "has divested the hero of his splendor, in upshot doing Iago's work" (Flower 433), yet recognizes that Othello "seems incapable of seeing himself except in grandiose terms" (Bloom 445). Worse, in declaring himself "one that loved not wisely but too well" and "one non easily jealous," Othello is guilty of "absurd blindness" and "outrageous self-deception" (Bloom 474). Othello'due south final words have, as Goddard notes, a "preternatural calm" (Goddard, Two 105), but is in that location "pathos in the eloquence" or "bombast" (Wells 256)? "His appeal is finally to the civilizing ability of language" (Garber 615). Othello's use of language is and so beautiful that G. Wilson Knight called it "the Othello music" (Garber 596).

Stratfordians and Oxfordians concord that despite the horrified spectators surrounding him, Othello, like Hamlet, directs his final speech to us (Garber 614, Ogburn and Ogburn 520). Read so, and as an autobiographical utterance from Lord Oxford, some of the dissonances resolve.

A Venetian witness to the suicide notes in despair, but oddly, "All that'south spoke is marr'd." Everything Othello said is corrupted? How and then? The statement has a sweeping quality that renders it more sensible if taken in a much wider context. The severity of this tragedy has made all linguistic communication itself corrupt somehow. All reports are erroneous. Truth and actuality are nearly inaccessible. What you will hear is non going to be the truth, Oxford suggests.

Cassio laments and eulogizes, less abstractly only as well oddly, "This did I fear, but thought he had no weapon; / For he was nifty of heart." I notice it hard to piece together all three components of this sentence to brand any stable sense. Mayhap all that'southward spoke is marred already. At any charge per unit, some may not have thought so, simply Oxford did have a "weapon" with which to practise some command over the terminal story. Some may call back that disconnecting the artist's proper noun from the title page does the job permanently, but Oxford buried enough materials then that with some serious textual excavating, a restoration can exist achieved.

Lodovico then addresses Iago: "O Spartan dog, / More fell than anguish, hunger, or the sea! / Expect on the tragic loading of this bed; / This is thy work." Asimov envisions an Iago probably grin at the tragic loading of the bed (633). He glosses "Spartan dog" as a bloodthirsty hound trained to hunt and kill (633). Only "Spartan" has another clan that has gone unnoticed. The ancient Spartans were famous for their laconic nature -- that is, of being of few words. When in the play recently Iago was asked the central question of "why," his answer was, "Need me naught; what you know, you know. / From this time forth I never will speak discussion" (Five.ii.303-304), an enigmatic and Spartan concluding utterance from this villain.

Lodovico continues: "To you, Lord Governor, / Remains the censure of this hellish villain, / The fourth dimension, the place, the torture, O, enforce information technology!" It is doubtful that torture will thing much. Iago has already been stabbed! You cannot faze this guy. Nearly inhuman himself, he seems immune to the forms of human suffering. "That Iago himself is trapped and is to be destroyed by torture must seem quite irrelevant to him. The victory is his" (Asimov 633).

With Lodovico left, here are the final lines from Othello: "Myself volition straight aboard, and to the country / This heavy deed with heavy centre relate" (Five.2.370-371). Thus Othello, like numerous other plays in the canon, ends with a promise of recounting, retelling the events we the audience have simply witnessed. These endings certify the experiences every bit narratives and look forward to their re-presentation. Further, in the Shakespeare tragedies, "retelling becomes the tragic hero's only path to redemption" (Garber 615).

Consider how focused Othello has been all along on narratives, or stories. Othello claims to have entertained Desdemona and her father, and to accept won the love of the one-time, with dramatic autobiographical stories of his adventures. Iago's success was in "constructing a narrative into which he inscribes ... those effectually him" (Greenblatt 234). And in terms of his cocky-fashioning, "not only does Iago mask himself in lodge as the honest ancient, but in private he tries out a bewildering succession of cursory narratives that critics accept attempted, with notorious results, to translate into motives" (Greenblatt 236). The infamous handkerchief has at least ane story attached to it, so even stage props in this play tin can be caught up in the rampant narrativizing. In this respect, the tragedy of Othello is that Othello allowed himself to submit to, essentialize, and participate in the generation of a narrative involving infidelity and uncontrolled jealousy. Once activated by Iago, the narrative did its work all also well. "Even with the exposure of Iago'due south treachery, and so, there is for Othello no escape -- rather a nevertheless deeper submission to narrative, a reaffirmation of the self as story, but now carve up suicidally between the defender of the faith and the circumcised enemy who must be destroyed" (Greenblatt 252). Othello, ultimately, is a tragic testament to the powerful concur a story can accept over a human soul.

* * * * *

"Tarry a little, in that location is something else," equally was one time said in Shakespeare's Venice. Correct afterwards Othello's final voice communication and his stabbing of himself, Lodovico had remarked, "A bloody period" (Five.2.357). Fifty-fifty if we take the word "period" equally temporal -- referring to a time flow -- there is an unmistakable finality to the utterance: "then ends a real crude patch for Cyprus." Just Lodovico probably means "catamenia," more appropriately, as "end-point." (Call back of the Weelkes madrigal examined past Altschuler and Jansen: "Thule, the Period of Cosmography" = "Iceland, the Finish-Point of the Globe.") In other words, "A bloody ending to a once noble general." More than significance has been recognized, though, by über-Stratfordian Greenblatt -- not, of class, in his simulated biography Will in the Globe, simply in his much more intelligent Renaissance Self-Fashioning. He calls Lodovico's remark "bizarrely punning" and says that it "insists precisely upon the fact that it was a speech, that this life fashioned as a text is ended every bit a text" (Greenblatt 252). Othello has ended his life as he led it: playing out his office in a fashioned narrative that bestows on him his identity.

Death is the last punctuation mark to a life. A catamenia is the terminal punctuation marker to a life lived as a narrative. But perhaps suicide is the act of wresting back basic control of the cease of that narrative. Shakespeare, we know, was tormented by the tyrannically obliterating narrative control that posterity would have (unless the Sonnets expressing this were indeed mere pen exercises). Oxford, we doubtable, had skilful reason to agonize about losing control of that narrative. And we, we happy few, we band of sisters and brothers, are commissioned to restore that narrative -- to pin the right story on the correct man. "He shall take a noble retentivity. Assistance."

FINAL PERSPECTIVE

The play demonstrates that "sometimes the heuristic reading may be the truthful reading, while the hermeneutic reading may offering simply illusory significance" (Sutherland 82). Humans depend on the stability in the reactions of those around them for their ain sense of identity (Wells 253). In the construction of the identities of selves and others, much depends on the attitude of the minds of others. Desdemona is a temptress to Iago, a lady to Cassio.

Shakespeare begins at a certain signal to explore evil in weird ways. Far beyond Richard III, but more than like Aaron in Titus Andronicus, Don John in Much Ado Nearly Zip and Iago seem to have no existent motivation that isn't trumped up equally an excuse after the hatred is underway. Iago has no redeeming qualities, and evidently no remorse. The Ashland Oregon Shakespeare Festival'southward Iago in 1999 was led offstage screaming "No!" -- a terrible directorial selection. Iago announces his silence and remains so -- he will never explain and e'er remain an enigma, and he inhumanly registers no real concrete pain -- witness his eerie reaction to Othello wounding him. There is nothing you lot can exercise to this guy.

Today Iago would be in advertising. Is information technology possible to explain him? Students in a prior form made suggestions and these were my responses:

- Is it cocky-involvement? In what? What does he derive satisfaction from and why?

- Is it revenge? Information technology's a fairly contrived and twisted insistence on injustice if this is his retribution -- and why all the other deaths vs. just Othello and Cassio if this were a focused vengeance?

- Is he insane (as the giggling Bob Hoskins portrays in the 1981 BBC production)? But what kind of mental/emotional disorder is this? What specific pathology?

- Yes, he'southward similar a spoiled brat but not 1 in a candy shop since he doesn't have interest in processed. Ah, but in controlling abstractly, yes!

- Evil? Similar "insane" doesn't quite explain specifically -- there are lots of "evil" presumably. But yes, some people are just evil -- no explanation, no unfortunate childhood traumas, just patently evil.

Wells sees him as "a surrogate playwright, controlling the plot, making it upward as he goes forth with improvisatory genius" (249) and retreating into silence at the end. Coleridge called Iago'southward excuses "the motive-hunting of motiveless malignity" -- he seems to bring up and then many spurious motives that they abolish each other out. Bloom says Iago has no inner self -- it's just an abyss. Iago does seem like perverse intellectual exercise with no sense of morality, as pure intellect cutting off from humanity, where cold "revenge" becomes a combination of intellect and detest, as Goddard feels (Goddard, II 76): "intellect and detest--the most annihilating of all alliances" (Goddard, II 78).

Goddard makes an eloquent case for the modern relevance of Iago:

The ideological warfare that precedes and precipitates the physical disharmonize ... ; the propaganda that prepares and unifies public opinion; the conscription, in a dozen spheres, of the nation's brains; the organization of what is revealingly known equally the intelligence service; only most of all the applied absorption of scientific discipline into the military attempt: these things, apart from the cognition and skill required for the actual fighting, permit the states to define mod state of war, one time information technology is begun, as an unreserved dedication of the man intellect to death and destruction.But that is exactly what Iago is--an unreserved dedication of intellect to expiry and destruction. To the extent that this is true, Iago is an incarnation of the spirit of mod war. (Goddard, Ii 78)

But the final words should concern the playwright. "For such an autobiographical artist as the earl of Oxford, farthermost agony and disturbance in life ultimately provided profound inspiration" (Anderson 118). Or, more than eloquently,

Literature's debt to Oxford's remorse is incalculable, but none would have accrued had Oxford not had the capacity to stand apart from his emotions and observe them with disengagement, plotting their dramatization and contriving the verbal alchemy with which he would capture, reshape, and refine reality, milling man lives, near notably his own, to artistic ends with no more attrition than Iago in manipulating his victims to his inscrutable purposes. (Ogburn 571)

Source: https://public.wsu.edu/~delahoyd/shakespeare/othello5.html

0 Response to "Demand Me Nothing: What You Know"

Post a Comment